YOU need to Validate Past Performance

You really have to dig on this. There is a company that burned me so badly that I have turned down jobs at agencies because the company was already there. They were the worst company ever, completely inept, but they continue to win contracts.

So YOU have to figure out if the company has a bad track record. You can’t wait for the acquisition process to reveal that an agency has skeletons in their closet. Think about what will happen during the acquisition process. You will ask the company to submit several references for their work. You will generate a form and send it to the Contracting Officer (COs) at those agencies. Those COs will send it back to you telling you the dates of work and that they did a fine job. This endlessly happens because companies are only going to give you references in which they are certain that they will get a glowing recommendation. I have personally followed up on tons of company references and I have never found one that the company gave me that had anything negative to say. So, you can participate in this farce of checking the past performance box, or you can take the initiative to really find out about a company’s past performance.

Also, I wish you could, but you can’t really count on the Past Performance Information Retrieval System (PPIRS) to surface negative performance information. The problem is twofold. First, let’s say that we have a good CO who is putting in the real performance information about a contractor. “They did x,y,z well, they did D,E,F poorly.” The problem is that before that content is committed to the system, PPIRS, it must be validated by the contractor. The CO inputs the content into the Federal Awardee Performance & Integrity Information System (FAPIIS), and then the contractor gets a notification of what was entered and reads it. If there is any negative information, even if it is true and accurate, the contractor will tell the CO that it is not acceptable and force the latter to change it.

Other people won’t say it, but the contractors force the CO to lie, or at least to water down the truth to such a degree that it ceases to be the truth. Now this doesn’t happen 100 percent of the time. If it did, then 100 percent of the IT projects would be completely FUBAR. But if, let’s be generous here, 30 percent of IT projects have a cost variance, a schedule variance or both, then 30 percent of the contractor performance in PPIRS should indicate some negative performance issues. But it doesn’t. Companies guard this PPIRS data against anything negative above everything else.

The solution to this problem is easy. Let the COs write whatever they want, and separately, let the companies write whatever they want. If a CO sees it one way and the company sees it differently, both can stand on their own and COs on future engagements can make up their own minds about the risk posed by a potential offeror. The one key thing that I would never give up on is the fact that if a “Notice to Cure” or “Stop Work Orders” have been issued, the exact copy of those notifications must be listed in the PPIRS record without any alteration.

The other big issues concerning past performance is what I would call a very unethical action. I have seen it happen on my project. In the scenario of a clearly under-performing contractor, the government just wants to cut our losses and move on. But remember, in contracts, everything can be negotiated.

EVERYTHING

Apparently, past performance information is ripe for negotiation as well. I saw a CO negotiate with a contractor for positive performance review after two stop-work orders had been issued and we were not renewing the options in a contract because they were so unbelievably terrible. In this situation the government provided the good performance information in exchange for the contractor delivering all data and documentation and a commitment to not sue us afterward. I was ashamed to be a Fed that day.

Years later I went in to PPIRS with the intent of finding this old information and shining a light on it. PPIRS is so messed up that, even when you know what you are looking for, you can’t find it. The contractor referenced above was not Lockheed Martin, but that company has dozens of different records in PPIRS. Every conceivable spelling, abbreviation and nuance in the name is in there. As such, if you want to find performance information about them or any other company, good luck finding which one.

In order to fix past performance we need to:

- Clean up the data in PPIRS. Each entity should be in there one and only one time. Information should be connected by EINs or TINs.

- Require all of the performance documents (Notices to Cure, Notices to Terminate, Stop Work Orders, etc.) be included in PPIRS.

- Require COs to input their past performance information and for the contractor to input their past performance information in a blind manner, and accept that they will sometimes tell different stories.

- Publish guidance that tells COs that it is unethical and unacceptable to negotiate the input of any information that is not 100% accurate and truthful in FAPIIS. Provide a bounty for contractors who identify COs who try to do this.

Give a Lot of Detail

Too frequently we hold information back from the solicitation. We might know a lot about what we want to build or buy, but we only post a work statement. My eyes start to bleed when I read work statements. They are dense and abstract. One of the best solicitations I developed had a ton of detail. I’ll be using this solicitation later as an example of how to evaluate offerors, but the starting point was particularly good. It included:

- Statement of Work

- Microsoft Project Plan

- Requirements Specification

- Project Management Plan

- Resource Assignment Matrix

- Concept of Operations

- Requirements Traceability Matrix

- Requirements Strategy

- Rough Order of Magnitude Estimate

If you want offers to come in clustered around where you think they should be, give them this much detail. Many contracting officers recommend against this. Their rationale is that industry is the experts and we should defer to the experts and let them propose solutions that are on the cutting edge. I reject that notion in its entirety. In 2015 GAO put IT acquisitions and operations on the High Risk List. I am inclined to try doing some things differently. As such, whenever someone gives you static for trying a different approach, point to this and tell them that what we have done before hasn’t been acceptable.

If you have information about the work that you want contractors to perform, you should put it out there.

Competition in Contracting

Take a moment to walk in someone else’s shoes. In this instance, let’s walk in the shoes of the program manager or account manager at some contracting company who may bid on your solicitation. Those shoes will likely be nicer than the shoes that you are currently wearing. Now they have met with you a couple times. You seemed to like them; they seem to be a good fit for what you want to do. They read your solicitation and they are assembling a proposal and their bid protest for you. (I will get to bid protests later, but now it makes sense for companies to build both during the proposal development phase.) In the purest of situations they develop their technical and cost proposal and send them in. Regrettably, it is rarely so pure. Instead, they want more information. They want to know:

- Who is the incumbent contractor, how long have they been there and how much do you like them?

- How active have you been in courting other vendors to consider this solicitation?

- What other type of work might you have going on?

Answers to these questions will help the contractor to figure out whether they want to bid and, if so, how to structure it. For example, if the government is in love with the incumbent contractor, it may not make sense to bid at all. Writing a proposal takes time and energy. A wise person makes those investments when there is a reasonable chance of winning. But if the government if so head-over-heels for the current contractor, it likely won’t matter how good a proposal is, they won’t win. This is a shitty scenario for the government. The incumbent contractor knows how much the government loves them, and they will do everything in their power to make sure the other vendors also know how much the government loves them. This will lead to less competition and as a result, the incumbent will likely be able to charge higher prices.

You may love the work a team of contractors does, but you need to keep that in context. Nobody is irreplaceable. The way that you keep prices low is when there is legitimate competition for the work. But we are lacking competition in a big way. Sometimes we don’t have competition because only one or two companies bid on the solicitation and sometimes we intentionally avoid competition with a Justification for Other than Full and Open Competition (JOFOC).

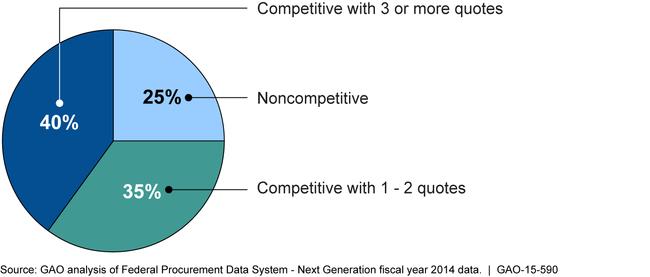

According to GAO, 25 percent have no competition, and 35 percent have a little competition. That represents a lot of awards with little to no competition. It means that we are getting ripped off. Recruit good companies for the work, but be sensitive about how they will use your accolades to freeze out other companies.

Also keep in mind that if you have lots of other IT work going on, your solicitation might be seen favorably if it gives them a foothold in the organization. For example, I have seen instances in which a company worked on a project that yielded virtually no profit, but it set them up with a more compelling case for a bigger project that the agency was going to engage. It is possible for government agencies to cultivate an environment in which you increase the competition and get better prices. As such, if you can sequence the work effectively you can create situations in which agencies will be actively working to cut their prices and beat the competition. But you must be careful.