The Situation Report: What NASA Can Teach Us About Government’s Innovation Potential

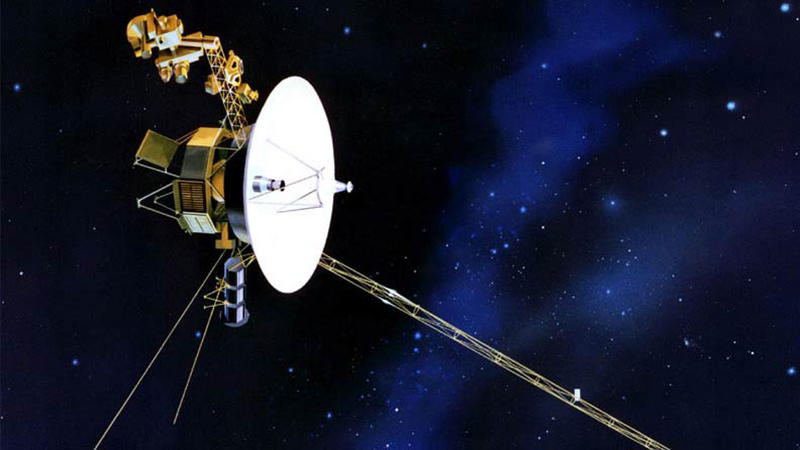

Voyager 2 spacecraft. (Photo: NASA)

The private sector innovation marketing machine is at it again. Congress should fund a new digital startup within the General Services Administration to focus solely on cybersecurity, according to a new set of policy recommendations released this week by the Information Technology Innovation Foundation.

“The goal of this initiative would be to incorporate private-sector knowledge and nongovernment culture into high-impact, high-priority federal government cybersecurity projects,” according to ITIF’s recommendation. “Members of this team could serve short-term stints based on new projects, agency needs, and available funding.”

There’s only one problem with this idea: It is based on a myth—the myth that the Federal workforce is incapable of matching the passion, ingenuity, and innovative spirit that has formed the centerpiece of the Federal contractor community’s marketing pitch for the past two decades. The government doesn’t need “nongovernment culture” to improve cybersecurity. What it needs is to recruit a workforce with a long-term vision of service and innovators driven not by the prospect of living a life of success but of living a life of meaning.

Nowhere is this example more apparent than at NASA. Take, for example, NASA’s Voyager 2 program. NASA scientists and engineers have been working on Voyager 2 for 40 years. It’s the only spacecraft to have ever visited Uranus and Neptune, and is currently making its way to interstellar space. The technical achievements recorded during missions to photograph Uranus, Neptune, and Neptune’s moons are without parallel and were done by career NASA employees.

Nowhere is this example more apparent than at NASA. Take, for example, NASA’s Voyager 2 program. NASA scientists and engineers have been working on Voyager 2 for 40 years. It’s the only spacecraft to have ever visited Uranus and Neptune, and is currently making its way to interstellar space. The technical achievements recorded during missions to photograph Uranus, Neptune, and Neptune’s moons are without parallel and were done by career NASA employees.

Engineers predicted storms weeks in advance on a planet more than 2 billion miles from Earth and advised where to point the spacecraft’s cameras. They also re-coded the cameras to produce sharp images in a place with little sunlight and as the spacecraft flew by at more than 35,000 mph. And it was all done with a 160 bits per second data link operating with the equivalent power of a refrigerator lightbulb.

What Can NASA Teach Us?

There’s no denying that NASA has had its ups and downs. But there’s also no denying that its successes far outpace its failures. Taking on missions where minor mistakes could destroy years of work requires a special kind of passion, leadership, and thirst for innovation.

And there may be something to the fact that the agency continues to place at the top of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey and the Partnership for Public Service’s Best Places to Work in the Federal Government rankings. The agency also ranked as the No. 1 “most attractive” employer for engineering students, according to global research and advisory firm Universum, and was named the second “Happiest Company in America” by CareerBliss rankings.

“The hundreds of employee reviews on employment websites tell the stories of employees who are fulfilled by the innovative, challenging, results-driven environment,” wrote Marta Wilson, a leading expert in leadership effectiveness, organizational improvement, and transformation strategy. “The most repeated theme among the reviews is: the people. The employees, both past and present, mention the pleasure of working in teams with their co-workers and leaders.”

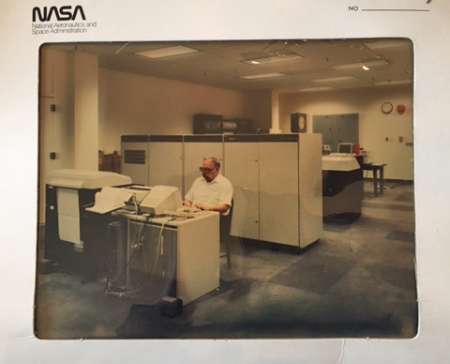

Edward Spear is a perfect example. He is one of the unsung heroes working behind the scenes to put John Glenn into space. He’s also the grandfather of MeriTalk reporter Morgan Lynch, who shared his story with The Situation Report.

It was the night before NASA would launch the first American into orbit, and the engineer who was tasked with coding the computer chips that programmed the launch wasn’t finished. The 31-year-old, Edward Spear, had returned from serving as an engineer for the U.S. Army in Korea 10 years before and now he was serving his country again at NASA.

A couple of hours before the morning’s launch on Feb. 20, 1962, Spear was satisfied with his work. He rushed the computer chips over to the launch site, only a couple of buildings away in Cape Canaveral, Fla. He returned to his desk, leaned back and tried to fall asleep, so tired that he didn’t mind missing the historic launch. Minutes later, a friend shook him awake and dragged him to the roof of the audience building to watch the rocket take off. Spear wasn’t nervous. The launch would be successful because he and his team had done their jobs well.

“He totally geeked out on the idea of working at NASA,” said Lynch. “He had a tie with rockets and satellites on it. He thought working at NASA was the coolest job in the world. And he probably thought that getting a job at NASA was the equivalent of ‘making it.’ ”

Is cybersecurity more difficult than putting John Glenn into space and getting him home safely? Is cybersecurity more technologically challenging than controlling a spacecraft, its code, and its sensitive instrumentation from 2 billion miles away? Is cybersecurity so overwhelmingly difficult that only private sector innovators are capable of succeeding? What is it about the culture of Silicon Valley today that makes it superior to the workforce culture that produced some of mankind’s greatest technological achievements?

The answer is nothing. The private sector’s innovation superiority is a myth. NASA is proof of that. The government doesn’t need techies who view service as a sacrifice to be endured for a couple of years. What really makes NASA different is the commitment of a workforce to a lifelong mission that is measured not in stock options, but in meaningful achievement.

Those people still exist.